The relationship between chickenpox and shingles, both caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), has long been a subject of medical inquiry and public concern. While chickenpox is a common childhood illness characterized by itchy skin rashes and fever, shingles, also known as herpes zoster, manifests as a painful rash in adulthood. One of the pressing questions in this domain is whether a person can contract chickenpox from someone with shingles. To address this question, it’s crucial to delve into the virology, epidemiology, and immunology of these conditions.

Virology of Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)

Varicella-zoster virus, a member of the herpesvirus family, is the infectious agent responsible for both chickenpox and shingles. After an initial infection, typically in childhood, the virus remains dormant in the sensory nerve ganglia. Later in life, under certain conditions such as immune suppression or aging, the virus can reactivate, causing shingles. This reactivation is thought to occur due to waning immunity to VZV over time.

Understanding Chickenpox Transmission

Chickenpox is highly contagious and spreads primarily through respiratory droplets or direct contact with the fluid from the blisters of an infected individual. The incubation period for chickenpox ranges from 10 to 21 days, during which the infected person may not display any symptoms but can still transmit the virus to others. Once symptoms appear, including the characteristic rash, the infected person remains contagious until all blisters have crusted over.

Shingles Transmission Dynamics

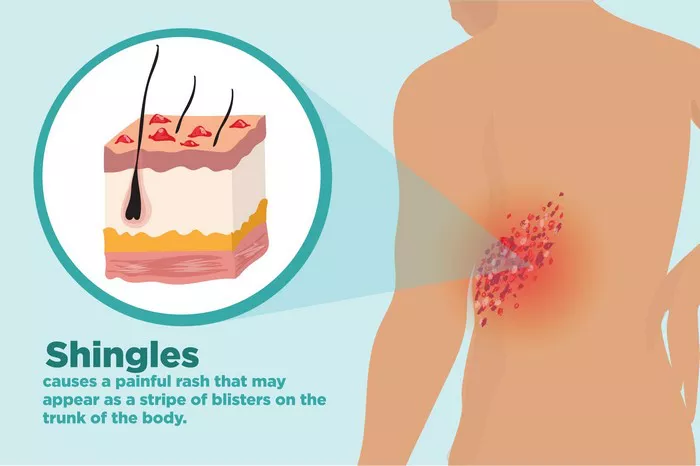

Shingles, on the other hand, is not directly transmissible from person to person. Instead, individuals who have never had chickenpox or the chickenpox vaccine can contract VZV from direct contact with the shingles rash. However, the transmission dynamics are different from those of chickenpox. The virus is less contagious in the case of shingles, as it requires direct contact with the fluid from the shingles blisters to spread the infection. Furthermore, individuals who develop shingles usually have a more robust immune response, resulting in lower levels of viral shedding compared to primary chickenpox infection.

Can Shingles Cause Chickenpox?

The question of whether someone can get chickenpox from someone who has shingles is multifaceted and requires careful consideration. While it is theoretically possible for VZV to be transmitted from the shingles rash to an individual who has never been infected with the virus, the risk is significantly lower compared to exposure to someone with active chickenpox.

Several factors contribute to this reduced risk:

1. Lower Viral Load: Individuals with shingles generally have lower levels of viral shedding compared to those with active chickenpox. As a result, the likelihood of transmitting enough virus to cause a primary infection in a susceptible individual is diminished.

2. Immune Response: Individuals who have been previously infected with or vaccinated against chickenpox have developed immunity to VZV. While this immunity may wane over time, it still provides some degree of protection against reinfection or primary infection with the virus.

3. Limited Transmission Window: The contagious period for shingles is shorter than that of chickenpox. Once the shingles rash has crusted over, the risk of transmitting the virus decreases significantly. In contrast, individuals with chickenpox remain contagious until all lesions have scabbed over.

Clinical Evidence and Epidemiological Studies

Clinical observations and epidemiological studies provide valuable insights into the transmission dynamics of VZV. While cases of individuals developing chickenpox after exposure to shingles have been reported, they are relatively rare compared to instances of chickenpox transmission from active cases. Moreover, many of these cases involve individuals who are immunocompromised or have other underlying health conditions that predispose them to VZV infection.

In a study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, researchers investigated the transmission of VZV from individuals with shingles to susceptible contacts. They found that while transmission did occur in some cases, the risk was significantly lower compared to primary chickenpox cases. Importantly, none of the individuals who developed chickenpox after exposure to shingles experienced severe complications, indicating a milder course of illness.

Implications for Public Health and Clinical Practice

Understanding the transmission dynamics of VZV is essential for informing public health strategies and clinical management. While the risk of contracting chickenpox from someone with shingles is lower compared to exposure to active chickenpox cases, certain precautions can help mitigate transmission:

1. Vaccination: Vaccination remains the most effective strategy for preventing both chickenpox and shingles. The varicella vaccine, routinely administered to children, has significantly reduced the incidence of chickenpox in many countries. Similarly, the shingles vaccine is recommended for adults aged 50 and older to reduce the risk of developing shingles and its complications.

2. Isolation and Hygiene: Individuals with shingles should avoid close contact with susceptible individuals, especially those who have never had chickenpox or received the vaccine. Practicing good hand hygiene and covering the shingles rash can help reduce the risk of transmission.

3. Antiviral Therapy: Early initiation of antiviral therapy for individuals with shingles can shorten the duration of illness and reduce viral shedding, thereby lowering the risk of transmission to others.

4. Education and Awareness: Healthcare providers play a crucial role in educating patients about the transmission dynamics of VZV and the importance of vaccination. Increasing awareness among the general public can help reduce misconceptions and promote preventive measures.

Conclusion

While the possibility of contracting chickenpox from someone with shingles exists, the risk is relatively low compared to exposure to active chickenpox cases. Factors such as lower viral load, preexisting immunity, and limited transmission window contribute to this reduced risk. Vaccination remains the cornerstone of prevention, offering protection against both chickenpox and shingles. By understanding the virology, epidemiology, and immunology of VZV, healthcare professionals can implement effective strategies to mitigate transmission and protect vulnerable populations.