Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a viral infection that causes a painful rash. It is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the same virus responsible for chickenpox. Once an individual contracts chickenpox, the virus remains dormant in the body and can reactivate years later as shingles. This article delves into the nature of the shingles virus, exploring whether it is considered a live virus and examining its implications for public health, treatment, and prevention.

The Varicella-Zoster Virus: A Double Life

1. The Dormant Phase

The varicella-zoster virus has a unique life cycle characterized by two distinct phases: the primary infection (chickenpox) and the latent phase, where the virus remains dormant in the nerve tissues. After an individual recovers from chickenpox, the VZV does not leave the body. Instead, it retreats to the dorsal root ganglia, clusters of nerve cell bodies located along the spinal cord. In this latent phase, the virus is inactive and causes no symptoms. However, it remains in a state of readiness, capable of reactivating under certain conditions.

2. Reactivation as Shingles

When the VZV reactivates, it travels along the nerve fibers to the skin, causing the characteristic shingles rash. This reactivation can occur due to various factors, including weakened immunity, stress, or illness. The resulting condition, shingles, is marked by a painful, blistering rash typically localized to one side of the body. The pain associated with shingles can be severe and long-lasting, a condition known as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

3. Is the Virus Alive?

To address the question of whether the shingles virus is a live virus, it is essential to understand what constitutes a “live” virus. In virology, a live virus refers to a virus capable of infecting host cells and replicating. By this definition, the varicella-zoster virus is indeed a live virus. Even during its latent phase, the virus retains the ability to reactivate and cause infection. Therefore, the VZV responsible for shingles is a live virus, albeit in a dormant state during certain periods.

Implications of a Live Virus

1. Transmission and Contagion

Understanding that the shingles virus is a live virus has significant implications for transmission and contagion. While shingles itself is not contagious, the varicella-zoster virus can be transmitted from a person with active shingles to someone who has never had chickenpox or the chickenpox vaccine. This transmission occurs through direct contact with the fluid from the blisters. The newly infected individual would develop chickenpox, not shingles, as their primary infection.

2. Risk Factors for Reactivation

Since the shingles virus remains alive within the body, certain factors can increase the likelihood of reactivation. Age is a significant risk factor, with the incidence of shingles increasing markedly in individuals over 50. This increase is likely due to the natural decline in immune function with age. Other risk factors include immunosuppressive conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, cancer treatments, and certain medications that weaken the immune system.

3. Symptoms and Diagnosis

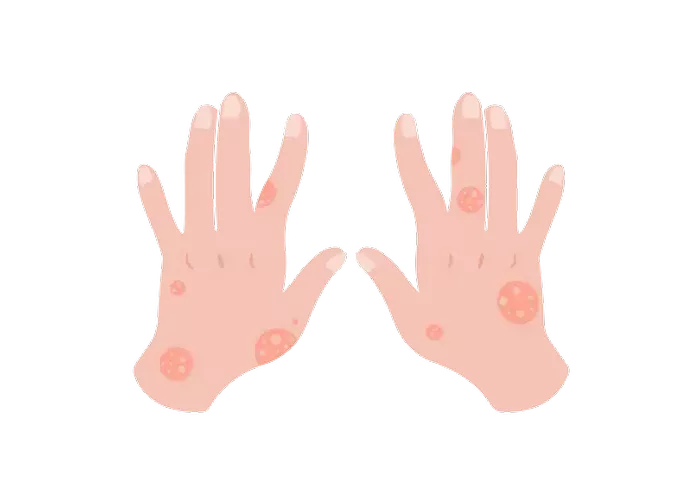

The symptoms of shingles are distinct and typically easy to diagnose. The rash often begins as a band or strip of raised dots on one side of the body. These dots then develop into fluid-filled blisters that eventually crust over. In addition to the rash, shingles can cause intense pain, itching, and sensitivity to touch. Diagnosis is usually based on the appearance of the rash and the patient’s medical history. In some cases, laboratory tests may be used to confirm the presence of the varicella-zoster virus.

SEE ALSO: How Long Do the After Effects of Shingles Last

Treatment and Management

1. Antiviral Medications

The primary treatment for shingles involves antiviral medications, which can help reduce the severity and duration of the symptoms if administered promptly. Common antiviral drugs used to treat shingles include acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. These medications work by inhibiting the replication of the virus, thus mitigating the outbreak.

2. Pain Management

Pain management is a crucial component of shingles treatment, given the significant discomfort the condition can cause. Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen, may be used to alleviate mild pain. For more severe pain, prescription medications, including opioids and anticonvulsants like gabapentin, may be necessary. Topical treatments, such as lidocaine patches, can also provide localized relief.

3. Postherpetic Neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a common complication of shingles, particularly in older adults. It occurs when the nerve fibers damaged during the shingles outbreak send exaggerated pain signals to the brain. Managing PHN often requires a multifaceted approach, including medications like antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and topical agents. In some cases, nerve blocks or other interventional procedures may be considered.

Prevention Strategies

1. Vaccination

Vaccination is the most effective strategy for preventing both chickenpox and shingles. The varicella vaccine, introduced in the 1990s, has significantly reduced the incidence of chickenpox. For shingles prevention, the shingles vaccine (Shingrix) is recommended for adults over 50 and those with weakened immune systems. Shingrix has proven to be highly effective, reducing the risk of shingles by over 90%.

2. Public Health Implications

The availability of effective vaccines has profound public health implications. By preventing the primary infection (chickenpox), the varicella vaccine indirectly reduces the reservoir of dormant VZV in the population, potentially lowering the incidence of shingles. Additionally, widespread use of the shingles vaccine among older adults can significantly reduce the burden of the disease and its complications, such as PHN.

3. Lifestyle and Health Maintenance

Maintaining a healthy immune system is crucial for reducing the risk of VZV reactivation. This involves regular exercise, a balanced diet, adequate sleep, and stress management. For individuals with chronic conditions or those on immunosuppressive therapies, working closely with healthcare providers to monitor and manage these conditions can also help reduce the risk of shingles.

The Future of Shingles Research

1. Advances in Vaccination

Ongoing research aims to improve shingles vaccines further and expand their availability. Scientists are exploring new vaccine formulations and delivery methods to enhance immunity and provide longer-lasting protection. Additionally, research into universal herpesvirus vaccines, which could protect against multiple herpesviruses, including VZV, holds promise for the future.

2. Understanding VZV Reactivation

Despite significant advances, much remains to be understood about the mechanisms underlying VZV reactivation. Researchers are investigating the genetic and immunological factors that contribute to the virus’s ability to remain dormant and later reactivate. Better understanding these processes could lead to novel therapies that prevent reactivation or target the virus more effectively during its dormant phase.

3. Novel Treatments

Innovative treatments for shingles and its complications are also under development. These include new antiviral drugs, gene therapies, and advanced pain management techniques. As our understanding of VZV biology and its interaction with the human immune system grows, these new treatments have the potential to offer more effective and personalized care for shingles patients.

Conclusion

The shingles virus, caused by the varicella-zoster virus, is indeed a live virus, capable of lying dormant in the body for decades before reactivating. This dual nature of the virus presents unique challenges and opportunities for prevention and treatment. Through vaccination, effective management of reactivation risk factors, and continued research, significant strides can be made in reducing the burden of this painful condition. As we advance our understanding of VZV and its behavior, we move closer to a future where shingles and its complications are significantly diminished.

Related Topics: